By Yasthiel Devraj & Kayleigh Pereira

“My mom’s place in Pretoria is cheaper to rent than this tiny apartment. And she has her own underground parking, a balcony and access to the communal pool.”

Josh lives in a tiny two-bedroom apartment behind The Mad Hatter, a few metres from Rhodes University’s campus. Truthfully, there is not much to his flat; the bedrooms are just big enough to comfortably accommodate a wardrobe, a double bed, a desk and a small ensuite bathroom. He does not have access to a garden or balcony and he does not have designated parking. For what it is, R3400 a month per person to live in a basic apartment in a small town is inarguably overpriced.

Using inflation as an excuse is a transparent fib that conveniently overlooks how easy it is for real estate agents and private renters take advantage of desperate students in this town.

In addition to the exorbitant rental rates, many students experience difficulties with their estate agencies when they leave their leases. Josh recalls his deposit being withheld for petty reasons. “They charged me for minor issues, some that were there before I moved in,” he says. Additionally, Oliver Momberg recalls his flatmate receiving her deposit several months after her lease ended.

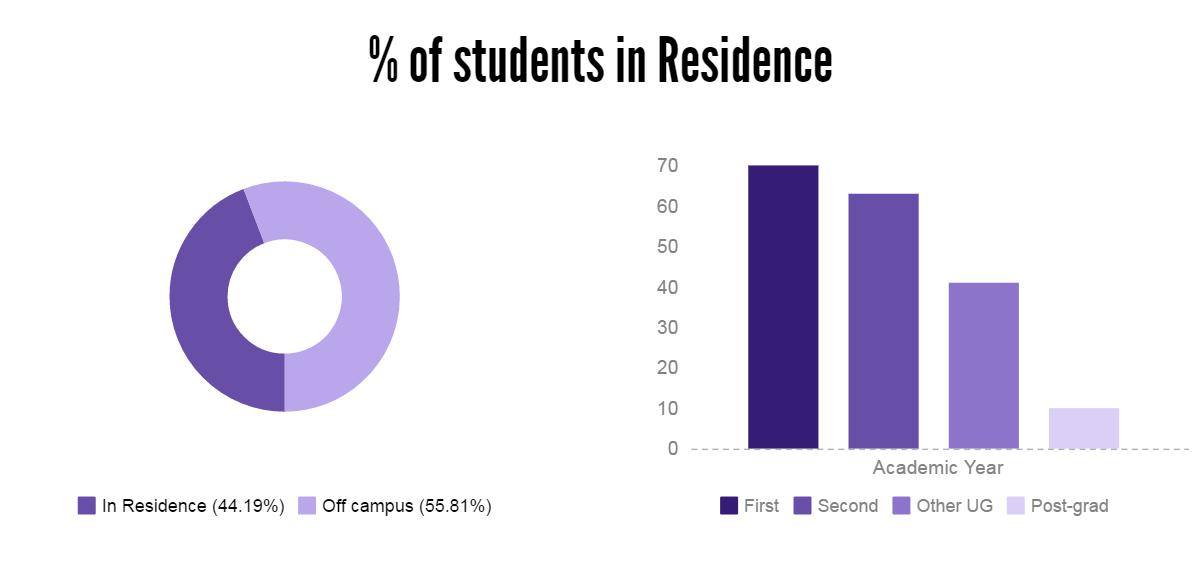

Approximately 55% of Rhodes students do not live in residences and accommodation presents a significant financial challenge for many students attending the University. This concern was highlighted in demands made during 2016’s #FeesMustFall protests, primarily concerning properties privately rented out by Rhodes University staff members.

Naledi Mashishi, who was involved in the FMF meetings that transpired last year, observed that there were two key aspects to the demands put forward regarding accommodation for students who were not living in residences. Firstly, leaders of the FMF movement appealed to lecturers to come forward as renters and openly identify themselves. Secondly, lecturers were expected to provide a number of basic living furniture, such as a bedframe and a refrigerator, when renting out to students.

As the renting of these places is considered to be a private matter, the university was not able to control the limits of these contracts. However, despite the demands being scrapped, the Rhodes management declared that they would work with the Oppidan Committee to help struggling students find accommodation that fits their financial constraints.

“What we’re asking for is an attitude of engagement,” explains student leader Christopher Morris, outlining the challenges faced by student activism on campus, and the deterioration of communications between protesting students and staff. “But what we find is that [University] management basically says: ‘this is how it is, you can like it or you can protest, and if you protest we will deal with you’ – all sorts of powerful ways that the University resorts to repression of our issues.”